Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, used to say that good monetary policy is boring. In fact, during 16 months of helping in the fight against Covid-19, central banks around the world have had a torrid time.

Central banks of both advanced and emerging market economies have learned some important lessons. Countries like Poland, a relatively small and open economy classified as an emerging market, have resorted to a judicious blend of conventional and unconventional monetary policies to carve out a measure of autonomy in a world dominated by the actions of larger economies.

Emerging market central banks have successfully widened their arsenal of monetary measures to mitigate the gravest economic effects of the crisis. One of these methods is to accrue foreign exchange reserves as a means of lowering the value of domestic currencies. This helps ensure that smaller countries do not suffer economic setbacks from larger countries’ massive quantitative easing through purchases of government bonds.

Until early 2020, unconventional monetary policies were confined to a few wealthy countries. The pandemic changed that, as shown by central and eastern Europe as well as around a dozen other emerging market economies. Central banks in Croatia, Poland and Hungary have bought significant quantities of their home government debt securities, increasing their balance sheets by 13%, 50% and 70% respectively since the start of the pandemic.

By crossing the Rubicon into unconventional policies, emerging market central banks have, in monetary terms, joined the nuclear arms club. This may confer prestige, but it doesn’t solve all problems. Conventional weapons are still needed.

By crossing the Rubicon into unconventional policies, emerging market central banks have, in monetary terms, joined the nuclear arms club. This may confer prestige, but it doesn’t solve all problems. Conventional weapons are still needed.

This becomes apparent by looking at the exchange rate effects of the larger countries’ QE. It is naïve to believe that smaller economies in the orbit of the giants will always benefits from QE-generated increases in demand enacted by their bigger neighbours. QE weakens the exchange rate of the larger country carrying it out. By enjoying a global or regional ‘exorbitant privilege’, larger monetary authorities can shift the burden of adjustment on to others.

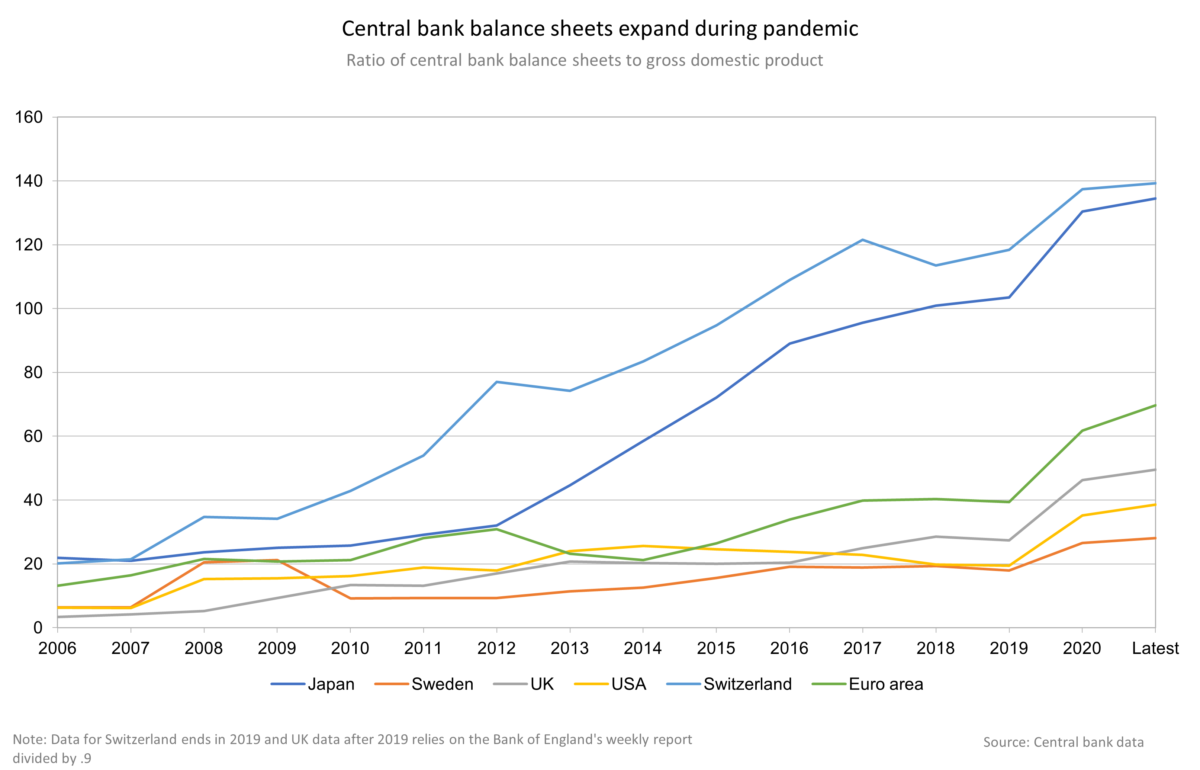

Guido Mantega, Brazilian finance minister in 2010, was correct in saying the exchange rate repercussions of the Federal Reserve’s QE amounted to ‘currency wars’. Since then, as a result of Covid-19, the amount of liquidity pumped into the world banking system has skyrocketed – with the largest economies in the vanguard by a wide margin. The Fed’s balance sheet of almost $8.1tn exceeds that of all the other western hemisphere economies. The European Central Bank’s balance sheet is twice as large as the GDP of the euro area’s largest economy, Germany. The total assets of the Swiss National Bank are equivalent to almost the combined GDP of Poland, Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia.

With the top five central banks’ total assets accounting for almost 28% of global GDP, smaller countries have a right to defend themselves, to avoid getting caught out by negative consequences. Philip Lowe, governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, is right in claiming that the actions of the larger players blunt the effects of his own bank’s bond purchases in lowering Australian interest rates and the Australian dollar.

Faced with this unbalanced ‘fight with the giants’, what should the emerging market central banks do? Simply scaling up unconventional policies may be counterproductive. Asset purchases aimed at stabilising domestic economies may end up destabilising home financial markets. Less developed economies face higher risks from mismatches. This is one reason why asset purchases in central Europe have been rather low. The Romanian central bank bought bonds worth less than 0.5% of gross domestic product. Hungarian and Polish purchases at around 5% and 6% of GDP respectively were well below that of the European Central Bank, whose bond purchases have been around 32% of euro area GDP.

Faced with this unbalanced ‘fight with the giants’, what should the emerging market central banks do? Simply scaling up unconventional policies may be counterproductive. Asset purchases aimed at stabilising domestic economies may end up destabilising home financial markets. Less developed economies face higher risks from mismatches. This is one reason why asset purchases in central Europe have been rather low. The Romanian central bank bought bonds worth less than 0.5% of gross domestic product. Hungarian and Polish purchases at around 5% and 6% of GDP respectively were well below that of the European Central Bank, whose bond purchases have been around 32% of euro area GDP.

Against this background, resorting to ‘conventional’ weapons makes sense. Foreign exchange intervention has become fashionable again to prevent domestic currencies from rising. Many counties in and around Europe have been intervening to mitigate upward pressure on their currencies, including Switzerland, Czechia, Israel and Poland. This is underlined by increases in these countries’ foreign exchange reserves.

Against this background, resorting to ‘conventional’ weapons makes sense. Foreign exchange intervention has become fashionable again to prevent domestic currencies from rising. Many counties in and around Europe have been intervening to mitigate upward pressure on their currencies, including Switzerland, Czechia, Israel and Poland. This is underlined by increases in these countries’ foreign exchange reserves.

For many years over the past half-century, Poland has been hampered by chronically low foreign exchange reserves. Now, with reserves (including gold) of almost $163bn against $128bn in 2019 and $95bn in 2015, Poland is, gratifyingly, among the world’s top 20 reserve currency holders. Part of this rise comes from the central bank selling zlotys and purchasing foreign currency. Some purists may complain about this. But the International Monetary Fund has given its blessing to these policies.

For many years over the past half-century, Poland has been hampered by chronically low foreign exchange reserves. Now, with reserves (including gold) of almost $163bn against $128bn in 2019 and $95bn in 2015, Poland is, gratifyingly, among the world’s top 20 reserve currency holders. Part of this rise comes from the central bank selling zlotys and purchasing foreign currency. Some purists may complain about this. But the International Monetary Fund has given its blessing to these policies.

Alongside the exchange rate, central banks have to be alert to the risks of rising inflation. For the time being, that appears under control, not least because today’s world is far more competitive than in the 1970s, when we last witnessed substantial inflation pressure. Once the post-Covid recovery appears sustainable, we can start deliberating about tightening policies. But central banks are a long way off that.

For the time being, we need to focus on keeping the recovery going – using all means possible. If this requires foreign exchange intervention to hold down otherwise unacceptable currency appreciation, then that is a legitimate line of defence.

The nuclear option of unconventional policies is part of our arsenal. Yet, to win wars, conventional armaments are often the key weapons. So, the best way forward for Poland and other emerging market economies is to use a mix of conventional and unconventional monetary policies. This is a key lesson from the crisis that will serve us well in coming years.

Adam Glapiński is President of Narodowy Bank Polski.

Note: Hungary’s bonds to GDP ratio was calculated using the Magyar Nemzeti Bank’s ‘general government’ balance sheet subposition, part of the ‘holdings of securities other than shares issued by residents’ position. Polish bond purchase calculations include purchases of government securities and government-guaranteed debt securities. The ECB’s ratio was calculated by adding all purchases conducted under the public sector purchase and pandemic emergency purchase programmes.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3qL6ZyQ

via IFTTT

No comments: